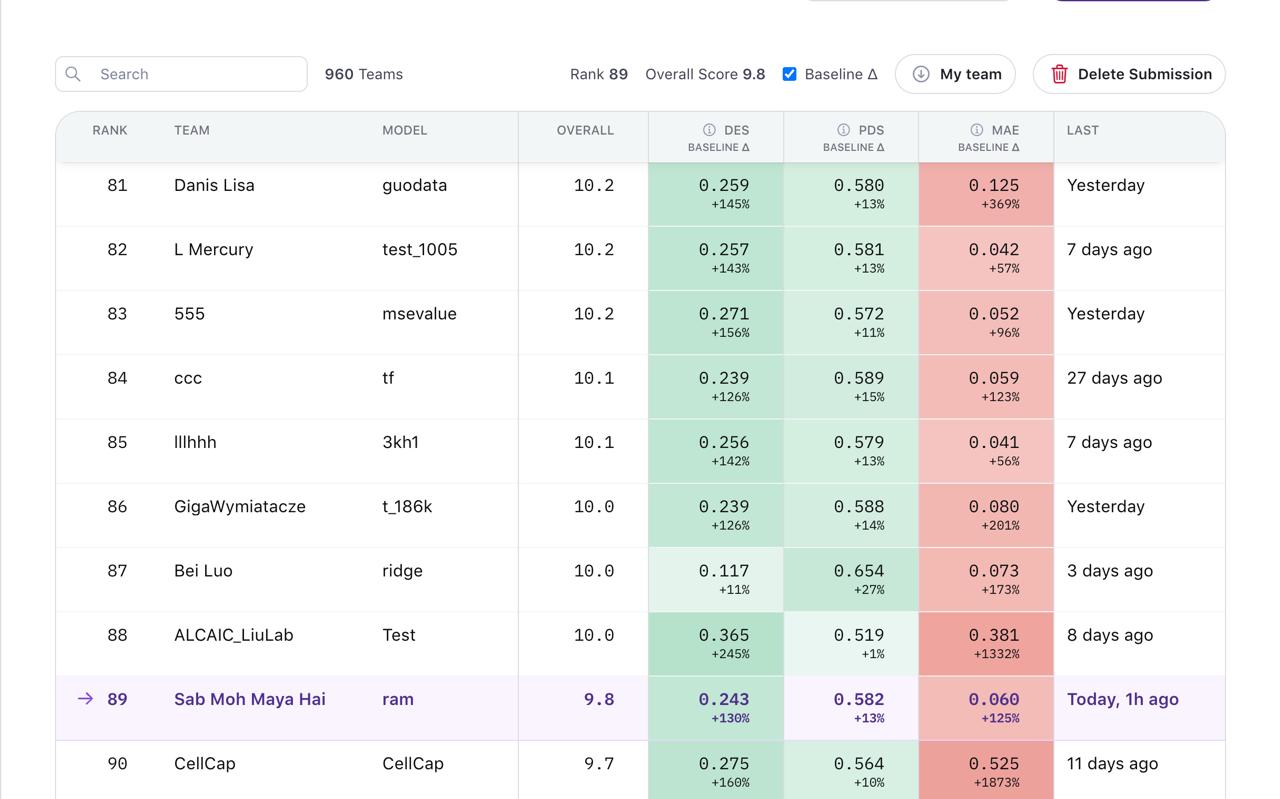

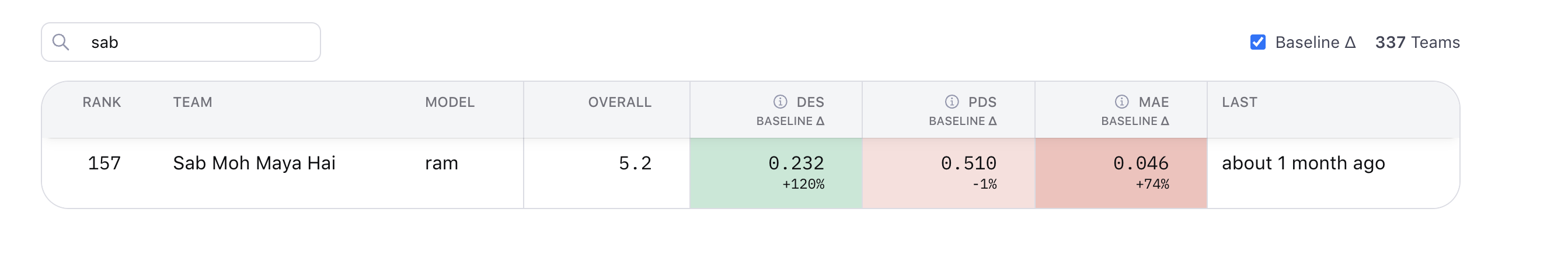

When Arc Institute announced the winners of the inaugural Virtual Cell Challenge at NeurIPS in December 2025, I wasn’t among them. I finished at rank 157 out of over 337 final submissions.

But here’s the thing - I’d been at rank 89 out of 960 teams on the validation leaderboard. Had something working. Then I changed strategies a week before the final deadline and watched my rank drop 68 positions.

This is that story.

Over 5,000 people from 114 countries registered for the challenge. More than 1,200 teams submitted results. Two $100,000 grand prizes were awarded, split between approaches so different it showed just how unsolved this problem really is.

I competed alone. Working evenings and weekends while juggling my day job as a Data Scientist at FUJIFILM Cellular Dynamics. No team to brainstorm with. No institutional compute budget. Just me, my laptop, whatever cloud credits I could afford, and a stubborn belief that I could build something real.

I did build something real. Then I broke it.

The Challenge: Can AI Replace an Actual Experiment?

The Virtual Cell Challenge wasn’t asking teams to optimize some abstract metric. Arc Institute was asking something way more ambitious: can a computational model actually stand in for a real Perturb-seq experiment?

Here’s the setup. You give the model a cell’s starting state - its gene expression profile across 18,000+ genes. Then you tell it you’re going to knock down a specific gene using CRISPR. The model has to predict what happens next to every other gene in the genome.

If you can do this reliably, you’re not just predicting numbers. You’re building a virtual laboratory. Test thousands of gene perturbations in silico before ever touching a petri dish. That’s the kind of capability that could transform drug discovery, just like AlphaFold transformed protein structure prediction.

Arc created a serious dataset for this. About 300,000 single-cell RNA-seq profiles from H1 human embryonic stem cells with 300 carefully chosen CRISPRi perturbations. They used 10x Genomics Flex chemistry - the high-quality stuff. The splits were balanced: 150 perturbations for training, 50 for validation, 100 for the final test.

What made it hard? H1 embryonic stem cells were deliberately chosen to be different from the cell lines most models had seen. No K562. No A375. This was a real test of whether your model learned biology or just memorized patterns.

Three Metrics That Don’t Always Agree

The Virtual Cell Challenge evaluated submissions on three metrics, and understanding how they relate became crucial to both my success and my failure.

MAE (Mean Absolute Error) is the accountant. Get the absolute numbers right. If your predictions are systematically off - wrong scale, wrong baseline, bad control handling - MAE exposes it immediately.

PDS (Perturbation Discrimination Score) is about direction. When you predict the effect of knocking down gene X, is your prediction closer to the true effect of X than to any other perturbation? This metric can expose models that predict bland, average-looking expression while getting the specific perturbation effects wrong.

DES (Differential Expression Score) is where biology comes in. It’s not just about getting numbers close. Did you identify the right genes as differentially expressed? Are they ranked correctly? Does the pattern look like real biology or statistical noise?

I learned these metrics were more than just numbers. They represented different ways biologists actually use Perturb-seq data. And optimizing for one could hurt the others if you weren’t careful.

What Got Me to Rank 89

My validation submission combined several ideas I’d been exploring: iterative refinement, biological knowledge integration, and memory-augmented architectures. Nothing revolutionary, but thoughtfully put together.

The High-Level Approach:

Rather than treating perturbation prediction as a single-shot problem, I modeled it as a process that unfolds over multiple steps. Some perturbations have simple, direct effects. Others cascade through regulatory networks, requiring more computation to fully resolve.

I incorporated biological knowledge - transcription factor relationships, protein interactions, pathway information - so the model wasn’t learning everything from scratch. And I used pretrained embeddings from foundation models trained on single-cell and protein sequence data to bootstrap representations.

Strategic Choices:

The approach that got me to rank 89 was fundamentally pseudobulk-based. I trained the model to predict population-level gene expression profiles after aggregating cells by perturbation. This aligned with how evaluation worked - the metrics were computed on pseudobulk aggregates.

I enforced important invariances:

- Control cells passed through unchanged

- Predictions framed as deltas from baseline, not absolute values

- Careful handling of raw count space

The model was complex enough to capture biological patterns but constrained enough to avoid overfitting.

It worked. Rank 89 on validation felt solid.

(I plan to release more technical details and code after further development)

The Mistake That Cost Me 68 Ranks

Here’s where I screwed up.

The validation leaderboard was based on pseudobulk predictions. My model was trained and tuned for pseudobulk. Everything was aligned. Then I started overthinking it.

I saw discussions on Discord about capturing cellular heterogeneity. About how averaging cells into pseudobulks loses information. About how the winning approaches might model the full distribution of cellular responses, not just population averages.

That logic made sense. If you can predict individual cell responses, aggregating them to pseudobulk should be more accurate than directly predicting pseudobulk, right?

So for the final submission, I switched my model to single-cell mode. Instead of predicting one pseudobulk profile per perturbation, I predicted individual cell responses and let the evaluation aggregate them.

The problem? I made this change with less than a week before the deadline. I didn’t have time to properly retrain the single-cell version. The model architecture could support both modes, but the training dynamics were completely different. Loss landscapes. Gradient flows. Convergence behavior. All different.

I submitted the hastily retrained single-cell predictions.

Final leaderboard: Rank 157.

Down 68 positions from validation.

What Actually Won

The winners took opposite approaches, and both succeeded:

Altos Labs (Generalist Prize) actually did model heterogeneity - but with a flow matching generative model pretrained on 7 million cells. They had the scale to make distribution modeling work. Their approach captured the full variability of cellular responses, not just averages.

TransPert (one of the top teams) stayed pseudobulk all the way through. Statistical framework using summary-level data with strategic loss function design. They didn’t try to model individual cells at all.

My mistake was clear: I tried to adopt Altos’s heterogeneity approach without Altos’s 7 million cell pretraining or their generative architecture. And I abandoned the pseudobulk focus that had been working for me, which TransPert proved was a winning strategy.

If I’d just submitted my validation approach - the pseudobulk model that got me to rank 89 - I’d have placed much better.

The lesson: when your validation approach is working, and you don’t have time to properly validate a new strategy, stick with what works.

Especially not a week before deadline. Especially not alone without a team to reality-check you.

Why I Couldn’t Compete with the Winners

Even with my best model, rank 89 probably wasn’t going to crack the top 10. The resource gap was real.

The Compute Gap

Altos Labs pretrained on 7 million cells from diverse sources including proprietary internal screens. I trained on whatever public datasets I could download and process on available compute. Their model saw perturbation responses across multiple cell types and conditions at a scale that teaches robust generalization. Mine saw a fraction of that.

Every training run I did was a commitment. When you can only afford 5-10 full experiments, you rely on intuition instead of empirical validation. The winners could run hundreds of experiments.

The Team Multiplier

Altos had ML scientists, computational biologists, probably wet lab collaborators. Division of labor. Parallel exploration. TransPert had five researchers across three institutions.

I was the ML engineer, the computational biologist, the statistician, the debugger, and the person second-guessing all my decisions. Solo means sequential exploration. That’s just physics.

The Data Advantage

Altos had proprietary perturbation screens they could use for pretraining. TransPert leveraged multiple reference cell lines with deep understanding of how effects transfer across contexts.

I had public data and what I could infer from literature. No internal experimental validation. No way to know if my model’s predictions were mechanistically plausible beyond what the metrics said.

What I Got Right (Validated by Winners)

Despite the resource gap, some of my core technical choices were validated by what the winners did:

- Delta-based framing (TransPert explicitly used this)

- Control invariance (both winning teams respected this)

- Strategic loss function design (TransPert optimized directly for PDS)

- Biological priors matter (Altos’s flow matching captured gene-gene interactions)

- Hybrid approaches over pure neural (exactly what the results showed)

My instincts about what would work were sound. I just couldn’t execute at the scale needed to compete with the winners.

What I Got Wrong

- Switching from pseudobulk to single-cell at the last minute

- Not having the scale to make heterogeneity modeling work

- Not committing fully to either the generative approach (Altos) or the statistical approach (TransPert)

- Being solo when this kind of work really benefits from team debugging and cross-pollination

Note: I’m keeping some technical details private for now. I plan to release a more detailed writeup and code after further development and validation.

What I Actually Learned

Technical Lessons

Yeah, I learned about delta framing, control invariance, biological constraints, iterative refinement, how to integrate foundation model embeddings with task-specific architectures. All valuable.

But the real lessons cut deeper.

Scale Has No Substitute

There’s no clever trick that replaces training on 7 million cells. No architectural innovation that compensates for 100× less compute. The winners had resources I couldn’t match, and it mattered more than being clever.

Good Ideas ≠ Good Execution

I understood what would work. Generative modeling. Massive pretraining. Capturing heterogeneity. But understanding and executing are completely different when you’re limited on compute, time, and iteration budget.

Solo Work Has Hard Limits

Not impossible. But the gap to well-resourced teams is real and growing. Without a team, you miss obvious things. Without compute, you can’t try enough ideas. Without time, you make mistakes like switching strategies too late.

Last-Minute Changes Are Dangerous

Rank 89 to 157 because I changed approach with inadequate validation time. This isn’t a minor lesson. It’s the core mistake that turned a decent showing into a disappointing one.

Competition Accelerates Learning

I learned more in eight-ten weeks of this challenge than I would have in six months of casual exploration. Having a benchmark, a leaderboard, and actual stakes forces discipline and clarity.

Writing This Matters

Most competition write-ups are from winners or they’re generic tutorials. There’s not enough honest documentation about why smart approaches didn’t work, about the resource gap, about the mistakes you make when you’re working alone and second-guessing yourself.

This post is my contribution to filling that gap.

Would I Do It Again?

Absolutely. Without hesitation.

Not because I think I’d win next time. Altos Labs still has their $3 billion endowment. Well-funded teams still have their compute clusters and proprietary data.

But because the alternative is worse.

Not trying means not learning. Not learning means staying where I am. The clarity I got from this challenge - about what works, what doesn’t, where I stand, what I need to improve - is worth more than avoiding the disappointment of rank 157.

I validated that my technical thinking is sound. The winning approaches used principles I’d independently discovered. Delta framing. Control invariance. Strategic loss design. Biological priors. When I get access to better resources, I’ll know what to do with them.

I’m part of a community now. 1,200+ teams worldwide working on virtual cells. My blog post, their experiments, the winners’ methods - it all contributes.

And I have a clear picture of what it takes to do state-of-the-art work. Not just algorithms. Resources. Collaboration. Infrastructure. Time. That honest accounting is valuable.

What’s Next

I’m taking everything I learned back to FCDI. We work on iPSC. The general principles I validated - incorporating biological knowledge, careful control handling, strategic loss design - all apply to our production systems.

I’m thinking differently about collaboration. Next big challenge, I won’t go solo. The team multiplier is real.

Long term, I want access to resources that let you compete at this level. Whether that’s through industry positions with real compute budgets, or academic collaborations, or building something of my own - I’m working toward it.

Arc Institute is running this as an annual challenge. Next year, I’ll be smarter. Better infrastructure. Maybe a team. Definitely not switching approaches a week before deadline.

The Bigger Picture

The Virtual Cell Challenge showed we’re making progress. STATE (Arc’s baseline) demonstrated 50% improvement in perturbation discrimination and 2× better differential expression identification compared to earlier approaches.

But the results also showed something humbling. Pure end-to-end neural networks aren’t yet consistently outperforming thoughtfully designed hybrid models. We’re not at the AlphaFold moment for cells. Not yet.

The winning approaches combined deep learning with classical statistics, biological priors with powerful representation learning. They showed that constraints and structure matter as much as scale.

That’s actually encouraging. It means there’s still room for clever ideas, not just bigger compute budgets. It means biology still has something to teach ML.

The virtual cell movement is real. Altos Labs, Recursion, Xaira Therapeutics, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Arc Institute - major players are betting on this. Datasets are growing. Models are improving.

We’re building toward a world where you can test drug candidates in silico before touching a patient. Where you can predict cellular responses to genetic interventions without running the experiment. Where computational biology isn’t just analysis but prediction.

I won’t be the one who gets there first. But I’ll be part of the collective effort that makes it possible.

Final Thought

I finished at rank 157. I’d been at rank 89 on validation. I made a strategic mistake that cost me 68 positions.

But I competed. I learned. I built something sophisticated enough to reach rank 89 as a solo participant. I documented the journey honestly - including the screwups.

The challenge felt fair. Arc designed it brilliantly (with a few metric hiccups along the way) and kept listening to community feedback throughout. The winners earned their prizes—and I walked away with something just as valuable: real clarity on where I stand and what I need to reach the next level.

For anyone thinking about entering next year’s challenge:

Do it. Even if you’re solo. Even if you don’t have massive compute. Even if you think you can’t win.

You’ll learn faster than you’ve ever learned. You’ll validate or invalidate your ideas against real data. You’ll join a community working on genuinely important problems. You’ll get honest feedback.

Just one piece of advice: if you reach rank 89 on validation with a working approach?

Stick with it.

Don’t switch strategies a week before deadline. Trust me on that one.

Learn from my mistake. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll crack the top 50. Or top 10.

Someone reading this will. And I’ll be cheering for you.

For Future Participants:

Start with Arc’s STATE baseline to understand the problem deeply. Study the winning approaches. Don’t overthink - sometimes simpler is better. And seriously: don’t change your core approach a week before deadline.

Trust your validation results.